BREAKING...

USC Diabetes Expert Joins Groundbreaking Stem Cell Initiative to Advance Next-Generation Diabetes Therapies

USC diabetes expert Anne Peters, MD, is joining stem-cell pioneer Charles “Chuck” Murry, MD, PhD, to advance a bold new therapy: creating insulin-producing cells from stem cells. Their cross-disciplinary collaboration could accelerate progress toward a future where a single procedure replaces daily insulin for people with diabetes. . .

Message from the Director Winter 2026

This has been a challenging year. Government policy changes sharply reduced medical and research funding, profoundly impacting our programs and prompting an all-hands effort to keep our staff employed.

Thanks to dedicated patient advocacy—and personal contributions from our team—we’ve been able to continue providing care and advancing research while we pursue new grants and now essential philanthropic support.

On the research front, progress continues. We’ve seen steady advances in incretin-based therapies using GLP-1 medications, with several promising compounds now in phase 2 and 3 trials. I am also thrilled to be partnering with Dr. Charles Murry at USC on pioneering work using stem cells to create insulin-producing beta cells. While immunosuppression remains a barrier, our collaboration aims to push past these challenges and bring this promising therapy closer to a life-changing clinical reality for people with diabetes.

We are also learning more about “global risk reduction”—treating blood pressure, lipids, glucose, and other factors together—which is helping people with diabetes live longer, healthier lives. I recently spent a clinic day with patients in their 80s and 90s who were thriving. Two decades ago, this would have been extraordinary.

I continue to work across both our Westside and Eastside clinics with exceptional colleagues. This year, our team published new research, and I was honored to receive an award from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

Your support has never been more critical. If you’d like to help sustain our important work during this time of transition, please consider supporting us through the donation link above. Your generosity directly strengthens our ability to care for people with diabetes in Los Angeles and beyond.

With gratitude,

Anne L. Peters, MD

USC Diabetes Expert Joins Groundbreaking Stem Cell Initiative to Advance Next-Generation Diabetes Therapies

Los Angeles, Calif. — Anne L. Peters, MD, Director of the USC Westside Center for Diabetes, has been invited to collaborate with Charles “Chuck” Murry, MD, PhD, a global leader in regenerative medicine, on an ambitious new effort to develop stem cell–derived therapies that could one day replace insulin injections for people living with diabetes.

Dr. Murry is Director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC and Chair of the Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine. Before joining USC, he led the Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Washington, where his research transformed the field of cardiac regenerative medicine. His work uses insights from early human development to create stem cells capable of becoming heart muscle, with the aim of healing damaged hearts. At USC, his lab continues to innovate in developing regenerative treatments for cardiovascular disease.

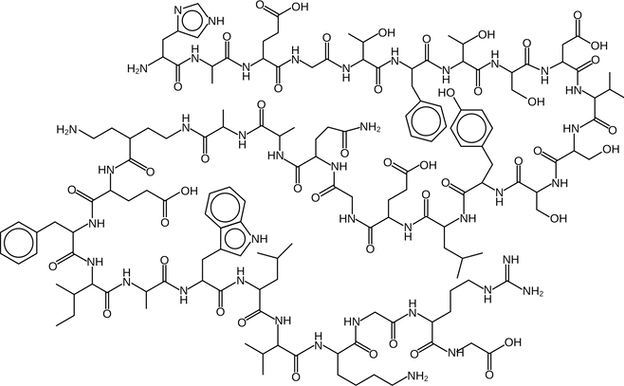

Dr. Peters will partner with Murry on his next frontier: using stem cells to create insulin-producing islet cells as a potential therapy for diabetes.

“I am excited about this partnership because I have seen patients who received donor islet transplants dramatically reduce—or even eliminate—their need for daily insulin,” said Peters. “Our vision is a treatment that could replace lifelong monitoring and insulin injections with a single procedure. It is an ambitious goal, but one that could transform lives.”

The Promise and Challenges of SC-Islet Therapy

Stem cell–derived islet (SC-islet) therapy aims to generate insulin-producing cells in the lab as an alternative to donor islet transplantation, which is severely limited by organ availability. Unlike donor islets, stem cells can be expanded to produce an unlimited supply of islet cells and engineered to reduce the risk of immune rejection.

While early clinical trials show promise, key challenges remain—among them preventing rejection without lifelong immunosuppressant medications and ensuring that transplanted cells function effectively and durably over time.

A Unique Collaboration to Accelerate Discovery

Combining Murry’s breakthroughs in cardiac regenerative medicine with Peters’ decades of clinical leadership in diabetes care creates a unique scientific partnership poised to accelerate progress. Over the past decade, the field of cardiac regeneration has advanced rapidly, offering powerful insights into tissue engineering and cell transplantation techniques—knowledge that may be directly applicable to islet cell therapy.

“This collaboration brings together two areas of expertise that have evolved in parallel,” said Peters. “By working across disciplines, we hope to speed the development of a therapy that moves beyond managing diabetes to fundamentally changing its course.”

Update: Understanding GLP-1 Medications and the Next Generation of Incretin Therapies

GLP-1 medications—widely recognized today through names such as Ozempic® and the dual-hormone therapy Mounjaro®—may seem new, but this class of incretin-based drugs has been part of diabetes care for nearly two decades. Clinicians at the USC Westside Center for Diabetes began using GLP-1 and related incretin therapies with the introduction of Byetta® almost 20 years ago. With this long history, endocrinologists have deep experience with how these medications work, how patients respond, and how to use them safely.

How GLP-1 and Incretin Medications Have Evolved

The earliest medication in this group, exenatide, was originally discovered in the saliva of the Gila monster and marketed as Byetta®, later followed by the once-weekly Bydureon®. These drugs mimicked part of a naturally occurring hormone called GLP-1. As research progressed, newer medications were developed that more closely resembled human GLP-1, including Victoza®, Trulicity®, and Ozempic®.

To improve clinical results, researchers combined two incretin hormones—GLP-1 and GIP—creating tirzepatide, sold as Mounjaro®. This dual-hormone approach has shown even greater benefits for blood glucose management and weight reduction. Today, scientists are exploring additional combinations, including medications that blend three incretin hormones, with several promising candidates currently in development.

What We Know About Safety

Recent studies show that Mounjaro® provides cardiovascular benefits and continues to demonstrate a strong safety profile. Earlier concerns about pancreatitis or medullary thyroid cancer have not been supported by current evidence.

Questions have also arisen about whether GLP-1 medications may worsen diabetic eye disease. In one Ozempic® study, a small group of participants with pre-existing retinopathy experienced worsening symptoms. It is still unclear whether this was caused by rapid improvements in blood sugar or by the medication itself. A dedicated study is underway to clarify this risk.

In the meantime, findings from real-world patient data have been mixed—some analyses suggest a possible association, while others do not. No increase in blindness has been observed, and some patients have experienced improvements in other eye conditions, such as macular degeneration. Clinicians continue to prescribe these medications to people with diabetic eye disease in coordination with their ophthalmologists.

What’s Next

A number of next-generation incretin therapies are now in clinical trials. Like the medications already on the market, they may cause gastrointestinal side effects, though early studies suggest these may be less pronounced. Their full benefits and tolerability will become clearer once they receive FDA approval and move into broader clinical use.

The USC Westside Center for Diabetes remains committed to evaluating emerging treatments and helping patients understand the safest and most effective therapies available.

Technology Update: How New Tools Are Transforming Diabetes Care

Advances in diabetes technology continue to reshape daily life for people with diabetes—and clinicians at the USC Westside Center for Diabetes are helping lead the way. While it’s hard to imagine returning to the days of finger-stick glucose checks, access to continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) remains critical, especially as coverage changes such as potential Medi-Cal limits could affect future availability.

Today, the center uses CGM technology with a wide range of patients, from those with prediabetes to individuals managing diabetes with insulin or non-insulin therapies. CGMs provide real-time glucose readings to patients and offer clinicians a detailed picture of glucose patterns to guide treatment decisions.

Expanding Access to Automated Insulin Delivery

Automated insulin delivery (AID) systems—which pair a CGM with an insulin pump guided by an algorithm—represent the next wave of diabetes management. Although not flawless, these systems are increasingly reliable and now approved for many people with type 2 diabetes who require insulin.

Research at USC has shown that diabetes technology can be used successfully across diverse patient populations, including individuals with limited numeracy or literacy skills. With additional hands-on training from diabetes educators, patients of all backgrounds can benefit.

Working as a volunteer consultant, Anne Peters, MD, has partnered with the Venice Family Clinic to demonstrate what is possible when advanced technology is brought into primary care. After Dr. Peters trained the clinic’s diabetes educators to use and adjust AID systems, the clinic has successfully started more than 100 under-resourced patients on AID therapy, resulting in significant improvements in glucose levels. The program is now being shared nationally as a model for how primary care clinics can expand access to diabetes technology with the guidance of a diabetes specialist.

What’s New in AID: Introducing Twiist

The newest AID system on the market is Twiist, built on the Loop algorithm originally created by parents in the DIY tech community. Twiist offers more customizable glucose targets—ranging from 87 to 180 mg/dL—but uses an older version of Loop software and includes an occlusion sensor that may trigger alarms when tubing becomes blocked. While this feature can help identify true pump issues, it may also lead to unnecessary alerts during everyday activities.

USC patients have not yet started using Twiist, and early reviews from outside users have been mixed. More updates will follow as the center gains hands-on experience.

Continuous Glucose Monitors: Still Improving

CGM technology continues to evolve, though accuracy and wear-time challenges remain. Dexcom’s newest sensors, previously affected by manufacturing issues abroad, are now being produced in the United States and are expected to offer improved reliability with a 15-day wear time.

The Libre 3 Plus is also becoming compatible with more AID systems, offering additional flexibility for patients who prefer that platform.

With new systems launching and existing tools improving, diabetes technology is entering an exciting new era. USC clinicians will continue monitoring developments and sharing updates as they work to ensure safe, effective, and equitable access for every patient.

Expert Perspective: Why more research and more effective screening protocols are needed for type 1 diabetes prevention

By Anne L. Peters, MD

For the first time, we have a medication that can meaningfully delay the progression of type 1 diabetes. Teplizumab, an immune-modulating therapy, can slow the transition from stage 2 type 1 diabetes—when autoimmune activity is present but insulin is not yet required—to stage 3, when daily insulin becomes necessary. In clinical trials, this delay has averaged about two years, and the drug is now under fast-track FDA review for people newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.

This represents real progress. For children, a delay in the onset of type 1 diabetes can make an extraordinary difference—not only medically, but emotionally and developmentally. Yet despite my optimism for pediatric use, I remain uncertain about how best to apply teplizumab in adults.

The Knowledge Gap in Adult-Onset Type 1 Diabetes

The fundamental challenge is that we know surprisingly little about the development of type 1 diabetes in adults. Many of my adult patients—especially those over age 35—progress far more slowly than children. Some do not require insulin for years; others need only very low doses once daily. Despite this, our primary research infrastructure, including TrialNet, focuses almost entirely on people up to age 45. As a result, we lack the evidence needed to determine how beneficial teplizumab truly is for adults with stage 2 disease.

Until we understand the natural history of adult-onset type 1 diabetes more clearly, it is difficult to define who will benefit most from a treatment designed to delay progression.

The Case for Universal Screening—and the Limitations

Another essential component of using teplizumab effectively is identifying who is at risk. This means screening children for type 1 diabetes autoantibodies. When two or more antibodies are present, the likelihood of developing type 1 diabetes increases significantly.

Screening is most often offered to children with a family history of type 1 diabetes, and I continue to recommend TrialNet for this purpose. But family history alone is not enough—most children who develop type 1 diabetes do not have a known relative with the condition. To truly identify those who might benefit from teplizumab, we would need to screen all children, and screen them repeatedly.

But universal screening presents its own challenges. Studies supporting this approach come primarily from Europe and have focused on non-Hispanic white populations. We do not yet know whether these findings translate to the diverse communities we serve in the United States. And because teplizumab delays—but does not prevent—type 1 diabetes, we must carefully weigh the benefits of broad screening against the logistical and emotional burden of testing children multiple times throughout their development.

Moving Forward With Careful Optimism

Teplizumab is a breakthrough, and its potential should not be understated. A two-year delay in the onset of type 1 diabetes can offer families time, stability, and a gentler transition into lifelong management. For children at risk, this can be profoundly valuable.

But until we close the significant gaps in our understanding of adult-onset type 1 diabetes, and until screening strategies are proven effective across all populations, we must approach widespread adoption with thoughtful caution.

Progress rarely comes all at once. Teplizumab is a milestone, and an important one. Now we must build the evidence and infrastructure needed to ensure we use it wisely—and equitably—for every person at risk.

News Archives

Winter 2023

Summer 2022

Winter 2022

Summer 2021

Winter 2021

Fall 2019

Summer 2019

Fall 2018

Summer 2018

Fall 2017

Summer 2017